Wednesday, March 29, 2006

Lorine, Lorine, the Thirties Machine

The first poem in the series strikes me as a great illustration of that shift in tone that comes with the Thirties, modernist wineskins for socialist wine. Kind of takes as its subject too Williams's idea about the intimate connection between speech forms and social structures. What do you think?

A country's economics sick

affects its people's speech.

No bread and cheese and strawberries

I have no pay, they say.

Till in revolution rises

the strength to change

the undigestible phrase.

Nice essay on Niedecker for the interested here.

1931

Niedecker somehow got the issue in Wisconsin and began corresponding with Zukofsky, from which all sorts of goodness and trouble flowed.

So … Feb. 1931.

Then they promptly fell into silence or neglect until the 1960s, when they got a second life. (Oppen and Rakosi spent their last decades here in San Francisco.)

So … hang in there.

Monday, March 27, 2006

Geek Alert

In 1937, O'Neill moved to Danville, CA of all places, and his house there--Tao House--is now a National Historic Site. Anyone been?

Friday, March 24, 2006

WCW on Mina Loy

"Mina was very English, very skittish, an evasive, long-limbed woman too smart to involve herself, after a first disastrous marriage, with any of us--though she was friendly and had written some attractive verse. I remember her comment on one of [Alfred] Kreymborg's books, Mushrooms--something to the effect that you couldn't expect a woman to take a couch full merely of pink and blue cushions too seriously. But when the Provincetown Players [best remembered for their association with the plays of Eugene O'Neill] has accepted Kreymborg's play, Mina had consented to take the lead. I was to play opposite her."

Which he did, convincing many on the Greenwich Village scene who saw it that he was half in love with Loy.

WCW on Marianne Moore

"...I believe in the main that Marianne Moore is of all American writers most constantly a poet--not because her lines are invariably full of imagery they are not, they are often diagrammatically informative, and not because she clips her work into certain shapes--her pieces are without meter most often--but I believe she is most constantly a poet in her work because the purpose of her work is invariably from the source from which poetry starts--that it is constantly from the purpose of poetry. And that it actually possesses this characteristic, as of that origin, to a more distinguishable degree when it eschews verse rhythms than when it does not. It has the purpose of poetry written into it and therefore it is poetry."

From The Autobiography (1951):

"Marianne Moore, like a rafter holding up the superstructure of our uncompleted building, a caryatid, her red hair plaited and wound twice about the fine skull, though she was surely one of the main supports of the new order, was no luckier than the rest of us. One night (Mina Loy was there also) we all met at some Dutch-treat party in a cheap restaurant on West Fifteenth Street or thereabouts. There must have been twenty of us. Marianne, with her sidelong laugh and shake of the head, quite childlike and overt, was in awed admiration of Mina's long-legged charms. Such things were in our best tradition. Marianne was our saint--if we had one--in whom we all instinctively felt our purpose come together to form a stream. Everyone loved her."

WCW on H.D.

"As we went went along--talking of what?--I could see that we were in for a storm and suggested that we turn back.

Ha!

She asked me if when I started to write I had to have my desk neat and everything in its place, if I had to prepare the paraphernalia, or if I just sat down and wrote.

I said I liked to have things neat.

Ha, ha!

She said that when she wrote it was a great help, she thought and practised it, if taking some ink on her pen, she'd splash it on her clothes to give her a feeling of freedom and indifference toward the mere means of the writing.

Well--if you like it.

There were some thunderclaps to the west and I could see that it really was going to rain damned soon and hard. We were at the brink of a grassy pasture facing west, quite in the open, and the wind preceding the storm was in our faces. Of course, it was her party and I went along with her.

Instead of running or even walking toward a tree Hilda sat down in the grass at the edge of a hill and let it come.

"Come, beautiful rain," she said, holding out her arms. "Beautiful rain, welcome."

And I behind her not inclined to join in her mood. And let me tell you it rained, plenty. It didn't improve her beauty or my opinion of her--but I had to admire her if that's what she wanted."

--from The Autobiography (1951)

WCW on TSE

from WCW, The Autobiography (1951):

"These were the years [Greenwich Village in the Teens] just before the great catastrophe to our letters--the appearance of T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land. There was heat in us, a core and a drive that was gathering headway upon the theme of a rediscovery of a primary impetus, the elementary principle of all art, in the local conditions. Our work staggered to a halt for a moment under the blast of Eliot's genius which gave the poem back to the academics. We did not know how to answer him."

Thursday, March 23, 2006

Williams on Pound, The Rematch

Here's an excerpt about Pound from Williams's sequence “A Folded Skyscraper” (1927):

“…thinking of Ezra Pound, our greatest and rightest poet, how excellent he is in his self-deception—opposed with a laugh to my fervent, my fierce, anger to have a country—speaking of his work, deriding me, saying that in the end his artificial pearl will be longer to last than anything I have made with all my striving—writing the greatest American poems today, his pearl-like cantos, so purely American—his self-deception, thinking how right he is in his self-deception that he had found poetry in the quattro cento in Dante, in them all of those old countries—when as a fact he had found poetry—how right he is a United States poet—when he thinks he has found poetry in the Renaissance, in his self-deception—for he HAS found poetry, an artificial pearly Pound, exile,--he has welded his material, he has what he has discovered, he has taken what there at least is—driven from my country that I strive so wildly to possess, he has taken the false, the make shift—the thing that they have here—made him take—not the thing I want, but the thing I want.—it is poetry, it is United States poetry—but he is deceived in thinking the medieval is the poetry, he is the making of the poetry, it is artificial pearly poetry because it is driven from being MY poetry—still I am right and still he is righter than I and still what I see exists and still he is right in doing poetry out of what is left—and still he is self-deceived—thinking of these things.”

Tuesday, March 21, 2006

Williams on Pound

I don’t know what to do with myself without our class meeting tonight. Thought I’d fill up the time by posting some of William Carlos Williams’s reflections on his contemporaries. They’re helpful for locating him in his world, but they’re also just fun and kind of gossipy—perfect for spring break!

From WCW’s autobiography, called (um) The Autobiography (1951), remembering Pound as an undergrad at Penn:

“Ezra never explained or joked about his writing as I might have done, but was always cryptic, unwavering and serious in his attitude toward it. He joked, crudely, about anything but that. I was fascinated by the man. He was the liveliest, most intelligent and unexplainable thing I’d ever seen, and the most fun—except for his often painful self-consciousness and his coughing laugh. As an occasional companion over the years he was delightful, but one did not want to see him often or for any length of time. Usually I got fed to the gills with him after a few days. He, too, with me, I have no doubt.”

“I could never take him as a steady diet. Never. He was often brilliant but an ass. But I never (so long as I kept him away) got tired of him, or, for a fact, ceased to love him. He had to be loved, even if he kicked you in the teeth for it (but that he never did); he looked as if he might, but he was, at heart, much too gentle, much too good a friend for that. And he had, at bottom, an inexhaustible patience, an infinite depth of human imagination and sympathy. Vicious, catty at times, neglectful, if he trusted you not to mind, but warm and devoted—funny too, as I have said. We hunted, to some extent at least, together, and not each other.”

Sunday, March 19, 2006

Tuesday, March 14, 2006

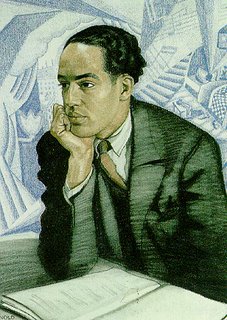

Final Note on Hughes

In comparison to some of the other writers who were also writing during this time, these very modern themes of isolation, the divided self, and alienation surface quite clearly in his work. I couldn't help but associate the construction of an American identity with these themes in the way that they permeate Hughes' writing. Unlike with Pound and Eliot, these themes seem to be a bit more prevalent in his work. Yet, there is also an eclectic distancing that I find really interesting in his work. I’m not sure if I would call it sardonic (?), but there’s something a bit closed to the reception of judgment. Just thought it was interesting.

I was curious if anyone had any thoughts about the essay Hughes wrote in Poetics. For some reason, it read more like more of an oratory speech to me than an essay, maybe because there are so many strident political themes Hughes tries to condense into his work. For example, he touches on issues of identity and the construction of the artistic Self and how they can potentially conflict in an unassuming fashion when the lack of a conscious identity is absent.

Hughes Poetics

However, I noticed for the first time (?) more of a sardonic overtone than perhaps I had been aware of in the past. I tried to relate this concept directly to the theme of presenting the American voice as something "other" where the struggle to bring it into manifestation creates a voice that is at once articulate, well crafted, and yet hints at something...closed (I hope I'm using the right word) and even regretful or lonely? Since isolation/the divided self surfaces in the works of so many other modern writers, I don't think it surfaced as much with some of the previous poets we have read. With Hughes, however, there is a very acute sense of alienation and even dismay that comes through in his poetry.

What were anyone's thoughts of the essay in Poetics? I thought Hughes made some interesting points on the nature of artist in the larger community. While he seems to want to claim an authentic black voice for poets, I wondered if all artists and writers don't also struggle collectively to find that authentic voice? But I guess his point is that the struggle to find that voice is magnified in that context. I liked that he sought to reclaim and celebrate the uniqueness of that experience, but I wondered specifically if he was writing for a particular audience since it seemed very "oratory" and read much more (to my ears) like a persuasive speech rather than an essay. All in all, though, there were sparks of real beauty in his poems and I enjoyed reading them.

Sunday, March 12, 2006

Critical responses to Hughes

My reaction to that was just ... !!! Crazy critics!! I have loved reading Hughes' work, and find it to be incredibly personal, powerful, and ... universal. It's as if he captures our common history -- the injustice, constraints, hope, and future -- and knits these qualities together.

It would be easy to dismiss the negative critical reactions as racist, so I've gone looking for more information. Keeping in mind also that I'm not a poetry student and have never studied Hughes before, so I could be missing the academic point!

I found a wonderful mini-site from the New York Times that has an archive of actual reviews of Hughes' work from 1930 to 1996. Also on this site are recordings of Hughes reading his own work -- including a fantastic reading of "The Negro Speaks of Rivers."

Poetics mentions a particularly scathing 1959 review of Selected Poems by James Baldwin, and the full review can be read here. Some excerpts that will give you a flavor for the review:

- ... his book contains a great deal which a more disciplined poet would have thrown into the waste-basket.

- I do not like all of "The Weary Blues," which copies, rather than exploits, the cadence of the blues ...

- Hughes is an American Negro poet and has no choice but to be acutely aware of it. He is not the first American Negro to find the war between his social and artistic responsibilities all but irreconcilable.

- I do not like all of "The Weary Blues," which copies, rather than exploits, the cadence of the blues ...

Ouch! So, why did the critics (or Baldwin in particular) hate Hughes' work so much? The most interesting answer I could find is in this 1969 review of an album of poetry, read by Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee (you may recall the wonderful actor Ossie Davis who died last year). The opener of this article captures it best ...

Critically, the most abused poet in America was the late Langston Hughes. Serious white critics ignored him, less serious ones compared his poetry to Cassius Clay doggerel, ands most black critics only grudgingly admired him. Some, like James Baldwin, were downright malicious about his poetic achievement. But long after Baldwin and the rest of us are gone, I suspect Hughes's poetry will be blatantly around, growing in stature until it is recognized for its genius.

Hughes's tragedy was double-edged: he was unashamedly black at a time when blackness was demode, and he didn't go much beyond one of his earliest themes, black is beautiful. He had the wit and intelligence to explore the black human condition in a variety of depths, but his tastes and selectivity were not always accurate, and pressures to survive as a black writer in a white society (and it was a miracle that he did for so long) extracted an enormous creative toll. Nevertheless, Hughes, more than any other black poet or writer, recorded faithfully the nuances of black life and its frustrations.

and ...

Critics have mistaken the simple form and language of Hughes's poetry for paucity of meaning. His real meanings are never that apparent and, in order to understand his poetry fully, one must have deep insight into ghetto life and psychology and an emotional tie.

To me, this really sums it up.

Saturday, March 11, 2006

Looking for Langston

Arnold Rampersad is Hughes’ leading biographer and editor of his Collected Poems, which has a handy set of notes in the back explaining the historical context and circumstances around many of the poems. If you’d like to know more about Hughes’ life and times, Rampersad’s the place to start. His bibliographies are up to the minute and should lead you on to any further reading you'd like to pursue.

Rampersad drew some heat with the first volume of the Hughes biography by asserting that Hughes was essentially asexual, despite evidence of affairs with both men and women. He researched and revised this opinion in the second volume, conceding that the most significant relationships in Hughes’s life were with men of color. Hughes himself kept up a formidable silence about his sexual preference while he was alive. Like Pound, H.D., Stein, Loy, Moore, and even Eliot in his odd way, Hughes wasn’t exactly the model of American family values. How significant is that for understanding modernism in American poetry?

For quick and dirty online resources, try here, here, and here (the mother of all bibliographies).

Hear Hughes describe & read one of his best-known poems here.

Research on the Harlem Renaissance is in full boom. The most elegant online site I could find about it is here. Contemporaneous with the Greenwich Village scene so central to the young Moore, Williams, and Stevens, Harlem formed an alternate vision of modernism that's desribed in intricate detail in David Levering Lewis's When Harlem Was in Vogue. The links (or lack thereof) between the Harlem scene and other strands in the postwar transatlantic avant-garde are explored in Houston A. Baker's Modernism and the Harlem Renaissance.

All for today ... think of me kindly, stuck in Indianapolis, on Tuesday!

Friday, March 10, 2006

Beaumont to Detroit: 1943

Beaumont to Detroit: 1943

Looky here, America

What you done done--

Let things drift

Until the riots come.

Now your policemen

Let your mobs run free

I reckon you don't care

Nothing about me.

You tell me that hitler

Is a mighty bad man.

I guess he took lessons

from the ku klux klan.

You tell me mussolini's

Got an evil heart.

Well, it mus-a been in Beaumont

That he had his start--

Cause everything that hitler

And mussolini do,

Negroes get the same

Treatment from you.

You jim crowed me

Before hitler rose to power--

And you're STILL jim crowing me

Right now, this very hour.

Yet you say we're fighting

For democracy.

Then why don't democracy

Include me?

I ask you this question

Cause I want to know

How long I got to fight

BOTH HITLER--AND JIM CROW.

Monday, March 06, 2006

Part 2

Adam

had ‘em.

My point being, condensation is a technical modality and not a philosophy. It has a limited range of usage. --Remember when you first got into Haiku’s and they were so great and you read them and you wrote them and then eventually you grew absolutely exhausted of their sparse imagery masquerading as philosophical treatises?

I am only saying this to start some talk about a larger picture of poetics that I see prevalent in the works of Stevens and Williams. Whereas authors like Stein and Pound, In My Opinion, destroyed convention and replaced it only with their egos or personae, Stevens and Williams fashion a philosophical (American) response to modernity. Agree or disagree?

Sunday, March 05, 2006

Romantic Imagination

Perusing several essays on Wallace Stevens I noticed some important ideas our class hasn't covered sufficiently. The first is the relationship between the Moderns and the Romantics. Reading Stevens and soon WC Williams it will be important to see how they built their ideas of the imagination (and poetry) in reaction to the Romantic's beliefs. I know all of you have studied Wordsworth and Shelley so if you could post some comments in response, telling me what you know about the Romantic's relationship with the imagination, this would be helpful to our discussion on Tuesday.

See Moore

In the intro, Shulman says something about Moore that reminds me of Stein’s emphasis on seeing objects clearly, or simply on attending to what’s in front of you (words as sounds, grammar as grammar, etc.), while also recalling Stevens’s fascination with perception in poems like “The Snow Man” or “Anecdote of the Jar”:

“’Art is exact perception’ is the opening line of Moore’s “Qui S’Excuse, S’Accuse,” first published in 1910, in the poet’s junior year at Bryn Mawr. The declaration is to become central, for seeing is at the heart of Moore’s poetry. Virtually all of Marianne Moore’s poems between January 1921 and June 1953 contain direct references to obtaining knowledge by sight. Hers is emphatically an art of exact perception: to feel deeply is to see clearly, to peer beyond surfaces, and to explore permanent truths. The poet amasses facts, remarks, observations, details from guidebooks and manuals, in pursuit of answers to the mysteries of modern love, of nobility, of timeless values that she probes and probes again.”

I wonder if this will be any help to us in thinking about Stevens.

Also can’t help including Moore’s first poem, written to Santa in 1895, when she was 8 (Warner is her brother). It’s already so Marianne Moore!

Dear St. Nicklus;

This Christmas morn

You do adorn

Bring Warner a horn

And me a doll

that is all.

Stevens v. Hemingway

Here's a story Hemingway wrote in a 1936 letter, recounting, of all things, a "Wallace Stevens evening." Stevens having come to Key West "sort of pleasant like the cholera."I so wish I could have heard just what Stevens said about Hemingway to have started that. In any case, this is, I think, a prime modernist moment.It starts with "my nice sister ... crying" over Mr. Stevens "telling her forcefully what a sap I was, no man, etc." [...]

Next, out in the rainy street, our hero "met Mr. Stevens who was just issuing from the door haveing just said, I learned later, 'By God I wish I had that Hemingway here now I'd knock him out with a single punch.'" This is hardly the Stevens we know, but Hemingway was not following his own counsel against putting real people into stories. The Mr. Stevens of the story next "swung that same fabled punch but fertunatly missed and I knocked all of him down several times and gave him a good beating." The location of Stevens's fall was "a large puddle of water."

Someone then requested that Hem take off his glasses, desiring "a good clean fight without glasses in it." Next "Mr. Stevens hit me flush on the jaw with his Sunday punch bam like that. And this is very funny. Broke his hand in two places. Didn't harm my jaw at all and so put him down again and then fixed him good so he was in his room for five days with a nurse and Dr. working on him."

Finally, "I have promised not to tell anybody and the official story is that Mr. Stevens fell down a stairs."

That's the story. It omits the shabby detail that Stevens was 56, Hemingway 36.

Big Wally

Wallace Stevens was a tall man, and fat, and enjoyed the sensual enticements of life just as much as his poetry suggests, against the backbeat of that tiny Episcopal Victorian bug in his ear buzzing about duty and responsibility and high tones just as insistently as it did in Marianne Moore’s.

Stevens and Moore both took a similar coy, eccentric stance toward the idea of American middle-class propriety—just as both chose to stay in America—and I hope you’ll keep Moore’s poems in mind as you read Stevens. The assertion of imagination, the exotic, of art itself as an alternative to the strictures that everyday U.S. life demands is a prominent feature of both poets’ writing.

Stevens is probably the most formally uninventive poet we’ll read all term, which just means he poured his new wine into more familiar wineskins than Stein, or Eliot, or Pound, or H.D,. or even the tidy but more syllabically-inclined Moore. Consider how Stein and Stevens represent two ends of the spectrum of American modernism: consider what the heck America, or modernism, even is.

The tensions in Stevens’s poetry point in so many different directions that in contemporary U.S. writing, both experimentalists and the more traditionally-inclined cite him as a major influence. Only Ashbery rivals Stevens I think in charting a territory so many divergent groups want to lay claim to.

The literature on Stevens is huge, and if you choose to write your paper on him there’s no dearth of poets and critics to put yourself in dialogue with (or to react against).

Here’s a tidy bibliography of major full-length studies on Stevens. and a more extensive one here.

The Modern America Poetry site has a fun gathering of “Recollections on Stevens By Contempoaries” in the Biography section. It’s a big (and perhaps exaggerated) part of the Stevens myth that he worked in corporate America and lacked a bohemian bone in his body. He’s up there with Eliot and Moore in defying notions, then and now, of what a poet’s life should be. What do you make of his image?

The Academy of American Poets has a thumbnail sketch of American Modernism along with the usual basic info on Stevens.

Hear Stevens read “The Snow Man” and other poems.

For the budding Stevens fanatics among you, you’ll probably want to get the coffee mug (or maybe explore an article from the Wallace Stevens Journal).

Friday, March 03, 2006

experimental jet set trash & no star

anyway. I'm not sure who i'm to e-mail regarding a reading-response blog so i'll just post it on here & delete it after i'm listed ... if you click on my name on the right (on the "contributors" list) it will give a bullshit profile of me & will have a list of blogs ... my reading-response blog is listed. unfortunately, it's about as eloquent as i usually am, so allow me to apologize in advance.

whenever i would walk out of a bar in pittsburgh's southside too many friends would start calling people drunk. bad idea. i'm not sure how this posting will go, but i'm listening to joan baez do a spanish cover of "no woman no cry"; that w/ a combo of too much whiskey & i fear i'm already talking nonsense.

there will be feasting & dancing in jerusalem next year.

cheers.

Wednesday, March 01, 2006

The other day I came across this resolution passed by the city of Lawrence, KS declaring an International Dadaism Month. The resolution includes the phrase "WHEREAS: zimzim urallala zimzim urallala zimzim zanzibar zimzalla zam."Also, please check out the dates in their Dada "month."

Also see this picture of Lawrence's mayor: "Boog" Highberger. Thank you, Boog, for bringing poetry to the people.